BAMBOO

NOTE: ANY PART OF THE GENERAL INFORMATION FOUND BELOW CANNOT BE DEEMED ANY SOLE CAUSE OF A FLOORING FAILURE WITHOUT PROPER TESTING AND INSPECTION.

CONTENT BELOW INCLUDES:

- MANUFACTURING BAMBOO FLOORING VIDEO

- GLOSSARY OF TERMS

- LOOKING FOR QUALITY BAMBOO

- BAMBOO BASICS

- PHOTOS - TYPES OF BAMBOO FLOORING AVAILABLE

- BAMBOO INSTALLATION & SPORTS FLOOR with VIDEO

- BAMBOO GLUE

- DYI REFINISHING

- PALM OIL RECYCLED *NEW

- PROFESSIONAL REFINISHING

ANY QUESTIONS FORWARD EMAIL TO: floorcovering@cox.net

1. MANUFACTURING BAMBOO PLANK FLOORING VIDEO

2. BAMBOO GLOSSARY (small)

A very brief Bamboo Glossary

- Auricle: an ear-like appendage that occurs at the base of some leaves.

- Cilium (pl. Cilia): one of the marginal hairs bordering the auricle.

- Caepitose: growing in tufts, or close clumps, as in bamboos with sympodial rhizomes.

- Clone: all the plants reproduced, vegetatively, from a single parent. In theory, all the plants from the same clone have the same genotype (genetic inheritance).

- Culm: the main stem of the Graminae (grasses). The stem of a bamboo is also referred as a cane.

- Culm Sheath: the plant casing (similar to a leaf) that protects the young bamboo shoot during growth, attached at each node of culm. Useful for distinguish species within a genus.

- Cultivar: seedling sports from a species which have multiplied from a single clonal source. A sport is a plant abnormally departing, especially in form or color, from the parent stock; a spontaneous mutation.

- Gregarious flowering: usually occurs when all plants in a single clone (which has been repeatedly divided and distributed) flower at about the same time.

- Gutation: water expelled over night as droplets from the tips of bamboo leaves.

- Internode: segment of culm, branch, or rhizome between nodes.

- Leptomorphic: temperate, running bamboo rhizome. It’s usually thinner then the culms they support and the internodes are long and hollow.

- Monopodial: describes the growth habit of the rhizomes of running temperate bamboos. The main rhizome continues to grow underground, with some buds producing side shoots (new rhizomes) and others producing aerial shoots (new culms).

- Node: the joint between hollow segments of a culm, branch, or rhizome; the point at which a rigid membrane of vascular bundles lends strength to an axis of bamboo by crossing it from wall to wall.

- Pachymorphic: describes the rhizomes of clumping bamboos. They are short and usually thicker then the culms they produce. These rhizomes have a circular cross-section that diminishes towards the tips. The internodes are short, thick (except the bud-bearing internodes, which are more elongated) and solid (with no cavities). See also Sympodial.

- Rhizome: a food-storing branch of the underground system of growth in bamboos from buds of which culms emerge above ground. Popularly known as rootstock, rhizomes are basically of two forms: sympodial (tropical, clumping, Pachimorph) and monopodial (temperate, running, Leptomorph).

- Rhizome sheathe: husk-like protective organ attached basally to each rhizome node.

- Running: describes a bamboo whose rhizomes have a markedly horizontal growth habit, and tend to develop along the surface of the soil.

- Shoot: the stage in the development of the bud before it becomes a culm with branches and leaves.

- Sulcus: a groove or depression running along the internodes of culms or branches.

- Sympodial: describes the growth habit of the rhizomes of caespitose bamboos. The rhizomes emerge from the lateral buds of other rhizomes, while the terminal buds produce new culms. See also Pachymorphic.

- Turion: the tender young shoot as it emerges from the ground without branches or leaves.

3. LOOKING FOR QUALITY - BAMBOO

There are a lot of misconceptions about bamboo flooring and a plethora of choices on the market. There are different ages of bamboo maturity and subsequent different hardness ratings,

different factory finishes and different manufacturing processes, making for a very confusing selection process. Many customers end up disappointed when they purchase a bamboo floor that is not high

quality and scratches very easily—sometimes before installation is even complete.

So what qualities should you look for? Most bamboo flooring is made from bamboo pieces glued together in alternating layers and then milled into flooring pieces.

Ideally, the bamboo should be at least four to five years of age in maturity so that it achieves a hardness rating of at least 1,400 psi on a Janka scale (harder than most oak flooring); some

flooring is being made out of only 2- to 3-year-old bamboo that is not fully mature and much softer on a hardness scale. Some customers have even blogged that

they can easily sink their fingernails into the flooring!

The moisture content (MC) should be 8 percent or less and consistent throughout the flooring boards. Consistency and even kiln drying is the key. There should be minimal color variation so

that the installers don't have to worry about drastic color patterning. The glues and finishes should be of high quality, contain at least one layer of a high-quality aluminum

oxide for increased scratch resistance and durability, and have low to no VOCs or formaldehyde. Some flooring

has only one or two layers of polyurethane, while others have five to six coats. Look for flooring that passes the strict CARB standards that California has set for indoor air

quality.

Stranded bamboo is more of a newcomer to bamboo flooring choices but is substantially stronger than traditional bamboo flooring. Made by compressing and binding together

strips and pieces of bamboo, stranded bamboo is about twice as strong as regular bamboo flooring, with hardness ratings in the 2,500 to 3,000 psi range. There are different manufacturing processes

used to make this type of bamboo flooring, so, again, there are different qualities to look for when purchasing it. MC is very important for this material and should, again, be consistent throughout

the batch and at 8 percent standard. Most moisture meters aren't set for bamboo flooring, not to mention stranded bamboo, so you will need to get a meter that can be set for these types of material

to get an accurate reading. The same qualities that you should look for in regular bamboo should also be reviewed for the stranded bamboo: Hardness, glues, finishes and MC are the big items to

ask

about.

As with any flooring, look for a good warranty in both the finish and structure of the flooring. Look for the documentation that shows FSC or another third-party certification to ensure Lacey

Act compliance and look for CARB compliance.

4. BAMBOO BASICS

BAMBOO BASICS

As the focus on environmental responsibility gains strength among consumers and the wood flooring industry, bamboo flooring continues to be in the spotlight. Love it or hate it, it's

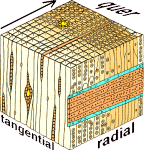

something most contractors will have to deal with sooner or later. Of course, bamboo is technically a grass. "Solid" bamboo is constructed of rectangles of bamboo glued together, either

horizontally or vertically. Engineered bamboo is constructed like any engineered floor with wood layers below a bamboo wear layer. The newest type of bamboo construction is strand-woven, a process in

which bamboo strands are saturated with an adhesive and fused together under enormous pressure, resulting in a product much harder than traditional bamboo flooring. Bamboo can be a great floor,

but there are some caveats to take into consideration. Following are some things I wish every customer would understand about bamboo. (These are general guidelines; always follow the

manufacturers' directions for the specific product you are installing).

1) Let it Expand

Many installers are in the habit of leaving expansion at the sides of boards but not at the ends. That's usually fine for a typical hardwood floor, but bamboo does expand and contract along its

length. Horizontal solid bamboo will expand and contract more than vertical bamboo, and strand-woven bamboo will expand and contract just like solid wood flooring.

2) Understand Janka

People should have realistic expectations of how a bamboo floor will perform. Sometimes the Janka numbers lead people to think a bamboo floor will be more durable than it actually is in real-life

situations. Bamboo fiber* are strong, but the lignins bonding them together are weak. In a Janka test, a smooth, round ball is pressed into the material. With bamboo, the fibers are springy and tend

to resist the ball. However, if you hit bambo with a sharp object—like a stiletto heel or a small rock in the sole of your shoe, it will cut into a bamboo floor more than it would in an oak

floor. An exception to this is strand woven bamboo, for which Janka tests accurately predict performance.

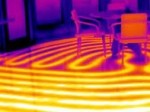

3) Watch The RH

With engineered products, it's important to keep bamboo's biological structure—strong fibers and weak bonding material between them in mind. When a bamboo wear layer is exposed to very low

relative humidity (RH), the fibers want to shrink and pull away from each other, but the fibers are held in place by the cross-ply structure of the engineered product, so they can't move. The weak

bonding lignins can then break, creating cracks in the wear layer. If there's a situation where the RH is likely to get very low, well-acclimated solid bamboo may be a safer option.

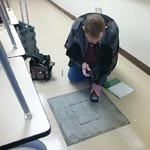

4) Measure MC Accurately

Make sure the manufacturer of your moisture meter has done the proper testing for bamboo so you know what the correct adjustment is on your moisture meter. If you're using a pin meter, as you poke

into the floor, make sure the prongs don't aross a glue line of the little rectangles glued together to form the floor, because you'll get a faulty reading. When you're buying bamboo, look for kiln

drying that meets typical American standards: within 6 to 8 percent moisture content (MC). Lots of product coming in from overseas is imported with a MC of up to 12 percent.

5) Acclimate as Necessary

Because solid bamboo flooring is made up of lots of little pieces of bamboo glued together, people often assume it doesn't need to be acclimated to the job site. Not true—even though there are many

small pieces, they are all oriented in the same direction and will expand and contract. Solid bamboo flooring tends to acclimate quickly (three to seven days is typical), but is does need to

ac-climate. Strand-woven bamboo also requires acclimation, and it acclimates very slowly. In extreme climates, it can take up to 30 days for a strand-woven bamboo floor to acclimate to a job site. As

with most engineered products of any species, engineered bamboo may not require acclimation (check with the manufacturer).

6) Know Your LEED Points

With the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification system, products may garner points under different categories. Under the "Rapidly Renewable Materials" credit, any solid

and strand-woven bamboo flooring earns points, but engineered bamboo does not, since it contains wood. Under the "Certified Wood" credit, bamboo flooring may earn points if it is FSC (Forest

Stewardship CounciO-certified, but the value of FSC-certified bamboo cannot be applied to both the "Certified Wood" and "Rapidly Renewable" credits—you have to choose one. Another credit

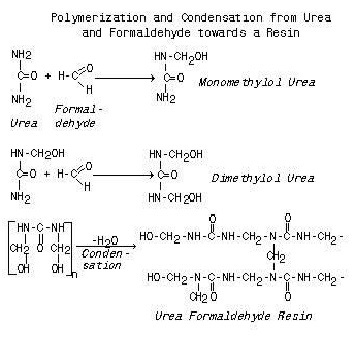

rewards products with no added urea-formaldehyde. Traditionally, the adhesives used to glue bamboo flooring together have been ureaformaldehyde adhesives, which tend to off-gas long after being

installed in a customer's home. Some bamboo products are now constructed with different adhesives, so they qualify for this credit. Strand-woven products are not constructed with urea-formaldehyde

and all qualify.

Dan Harrington

Director of product development

Richmond, Calif. based EcoTimber.

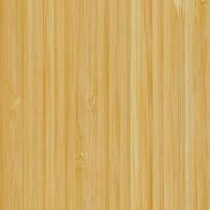

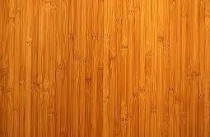

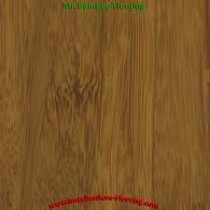

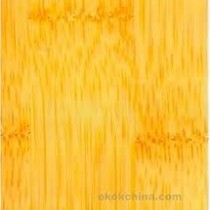

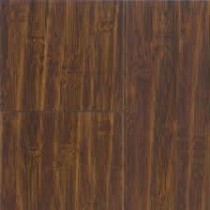

5. PHOTOS - TYPES OF BAMBOO FLOORING AVAILABLE

6. INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS

Installation Instructions

Before You Begin

Smith and Fong Plyboo® Bamboo flooring products are a jobsite inspection of your flooring should be performed for grade, color, finish and quality. Ensure adequate

lighting for proper inspection. If you find an irregularity in your flooring, please contact ll quality inspected before packaging and shipping. Nevertheless, a finalSmith & Fong immediately for

replacement. We cannot accept responsibility for flooring installed with visible defects.

Jobsite Requirements

Prior to installation of any flooring, the installer must ensure that the jobsite and subfloor meet the requirements of these instructions. Smith & Fong is not

responsible for floor failure resulting from unsatisfactory jobsite and/or subfloor conditions.

Plyboo® flooring should be one of the last items installed on any new construction or remodel project. All work involving water or moisture should be completed before

floor installation.

Room temperature and humidity of installation area should be consistent with normal, year-round living conditions for at least a week before installation. Room

temperature of 60-70¹F and humidity range of 40-60% is recommended.

Store your Plyboo® flooring at installation site for 72 hours before installation to allow flooring to adjust to room temperature and humidity. Do not store directly

on concrete or near outside walls. This flooring may not be acceptable for full bathroom installations because of moisture associated with such locations.

Acceptable Subfloor types:

• Plywood or OSB 3/4"

• Concrete slab

• Existing wood floor 3/4" or greater

Subfloor must be:

• Structurally sound

• Clean: Thoroughly swept and free of all debris

• Level: Flat to 3/16” per 10-feet radius

• Dry: Subfloor must remain dry year-round. Moisture content of wood subfloor must not exceed 12%, concrete moisture content must not exceed 3 lbs.

Wood Subfloors must be dry and well secured. Nail or screw every 6” along joists to avoid squeaking. If not level, sand down high spots and fill low spots with an

underlayment patch.

Concrete must be fully cured, at least 60 days. If not level, grind down high spots and fill low spots with leveling compound. Must be flat to 3/16” per 10 foot radius.

Do not install on concrete unless you are sure it stays dry year-round. All concrete must be tested for moisture.

Getting Started

Remember to begin installation next to an outside wall. This is usually the straightest and best reference for establishing a straight working line. Establish this line

by measuring an equal distance from the wall at both ends and snapping a chalkline. The distance you measure from the wall should be the width of a plank plus about *” for expansion space. If outside

wall is out of square, adjust working line to make it straight for the rest of your installation.

Gluing Down Installation

• Bostik’s Best Urethane Adhesive is our recommended adhesive. Read adhesive instructions carefully for proper trowel size and adhesive set time. Never use the “wet lay”

or “loose lay” method of installing. This is when you install the flooring immediately after spreading adhesive. This method will trap moisture under the floor and could cause the flooring to

warp.

• Starting at outside wall, spread as much adhesive as can be covered by flooring in one hour (or as recommended by your adhesive instructions). Spread with trowel at a

45¹ angle.

• Once adhesive has tacked, lay the first row of Plyboo® and continue laying flooring until adhesive is covered. Always check your working lines to be sure the floor is

still aligned. Be careful not to let installed floor move on the wet adhesive while you are working.

• When first section is finished, continue to spread adhesive and lay flooring section by section until installation is complete. Remove any adhesive that gets on

flooring surface immediately.

• Always leave at least a 1/2” expansion space between flooring and all walls and vertical objects (such as pipes and cabinets). Use wood or plastic spacers during

installation to maintain this expansion space.

• Walk each section of flooring foot-by-foot or roll within the adhesive working time to ensure solid contact with the adhesive. Flooring on perimeter of room may

require weighting until adhesive cures enough to hold them in place.

Finishing the job

• Remove expansion spacers and install base and/or quarter round moldings to cover the expansion space.

• Install any transition pieces that may be needed (reducer, T-moldings).

• Do not allow foot traffic or heavy furniture on floor for 24 hours or as adhesive manufacture requires.

• Vacuum your floor to remove any dirt or debris.

Cleaning and Maintenance

The maintenance program for Plyboo® flooring is designed to be user friendly. The latest advances in urethane technology are used in our manufacturing process to help

aid product performance and maintenance. The following simple steps should be used to ensure the best performance and appearance. The use of other products like wax, water or oil soaps should be

avoided.

After your floor has been installed, floor protectors should be placed under the legs of chairs and tables. Doors leading to outside should have floor mats placed both

inside and out.

Your floor should be cleaned weekly with the use of a suction vacuum, no abrasive rotary brush vacuums, to remove grit and debris from the surface of the flooring.

Higher traffic floors may require more frequent cleaning to keep floor free of grit and abrasive debris that can damage your floor and finish.

Every other week: We recommend the Bona-X Cleaning System. Bona-X will remove minor scuffs and foot traffic film

with an odorless VOC compliant product. The use of this product will not create future maintenance issues if and when re-coating the floor becomes necessary. This system includes a dry floor mop and

handle and a spray bottle of cleaning agent. Simply spray a small quantity of cleaning agent on floor surface and dry mop.

If there are areas that will not clean up with the Bona-X System, the use of Goof-Off will. Goof-off is a water-based cleaner that will remove paint, ink, adhesive

residue, and chewing gum without harming the factory finish. This product is available over the counter at most building material or paint stores.

Refinishing:

When refinishing is necessary and the floor has been maintained properly, it can easily be recoated by a process of cleaning, light abrasion and reapplication of an

appropriate finish material. We recommend a system employing an initial coat of Bonatech Prep Sealer, undercoat with two top coats of Bonatech Mega Finish. For further information, please contact us

at our toll free number, 866-835-9859.

VIDEO

SPORTS FLOOR INSTALLATION VIDEO http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=8w6YCEY63zc

Bamboo Around 92 genera and 5,000 species

Bamboo is a group of perennial evergreens in the true grass family Poaceae, subfamily Bambusoideae, tribe Bambuseae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family. In bamboo, the internodal regions of the stem are hollow and the vascular bundles in the cross section are scattered throughout the stem instead of in a cylindrical arrangement. The dicotyledonous woody xylem is also absent. The absence of secondary growth wood causes the stems of monocots, even of palms and large bamboos, to be columnar rather than tapering.

Bamboos are some of the fastest growing plants in the world, as some species have been recorded as growing up to 100 cm (39 in) within a 24 hour period due to a unique rhizome-dependent system. Bamboos are of notable economic and cultural significance in South Asia, South East Asia and East Asia, being used for building materials, as a food source, and as a versatile raw product.

More than 70 genera are divided into about 1,450 species.[3] Bamboo species are found in diverse climates, from cold mountains to hot tropical regions. They occur across East Asia, from 50°N latitude in Sakhalinthrough to Northern Australia, and west to India and the Himalayas. They also occur in sub-Saharan Africa, and in the Americas from the Mid-Atlantic United States south to Argentina and Chile, reaching their southernmost point anywhere, at 47°S latitude. Continental Europe is not known to have any native species of bamboo.

There have recently been some attempts to grow bamboo on a commercial basis in the Great Lakes region of eastern-central Africa, especially in Rwanda. Companies in the United States are growing, harvesting and distributing species such as Henon and Moso.

Bamboo is one of the fastest-growing plants on Earth with reported growth rates of 100 cm (39 in) in 24 hours. However, the growth rate is dependent on local soil and climatic conditions as well as species, and a more typical growth rate for many commonly cultivated bamboos in temperate climates is in the range of 3-10 cm (1-4 inches) per day during the growing period. Primarily growing in regions of warmer climates during the late Cretaceous period, vast fields existed in what is now Asia. Some of the largest timber bamboo can grow over 30 metres (98 ft) tall, and be as large as 15-20 cm (6-8 inches) in diameter. However, the size range for mature bamboo is species dependent, with the smallest bamboos reaching only several inches high at maturity. A typical height range that would cover many of the common bamboos grown in the United States is 15-40 feet, depending on species.

Unlike trees, individual bamboo culms emerge from the ground at their full diameter and grow to their full height in a single growing season of 3–4 months. During these several months, each new shoot grows vertically into a culm with no branching out until the majority of the mature height is reached. Then the branches extend from the nodes and leafing out occurs. In the next year, the pulpy wall of each culm or stem slowly hardens. During the third year, the culm hardens further. The shoot is now considered a fully mature culm. Over the next 2–5 years (depending on species), fungus and mold begin to form on the outside of the culm, which eventually penetrate and overcome the culm. Around 5 – 8 years later (species and climate dependent), the fungal and mold growth cause the culm to collapse and decay. This brief life means culms are ready for harvest and suitable for use in construction within about 3 – 7 years. Individual bamboo culms do not get any taller or larger in diameter in subsequent years than they do in their first year, and they do not replace any growth that is lost from pruning or natural breakage. Bamboos have a wide range of hardiness depending on species and locale. Small or young specimens of an individual species will produce small culms initially. As the clump and its rhizome system matures, taller and larger culms will be produced each year until the plant approaches its particular species limits of height and diameter.

Many tropical bamboo species will die at or near freezing temperatures, while some of the hardier or so-called temperate bamboos can survive temperatures as low as −29 °C (−20 °F). Some of the hardiest bamboo species can be grown in places as cold as USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 5-6, although they typically will defoliate and may even lose all above-ground growth; yet the rhizomes will survive and send up shoots again the next spring. In milder climates, such as USDA Zone 8 and above, some hardy bamboo may remain fully leafed out year around.

Most bamboo species flower infrequently. In fact, many bamboos only flower at intervals as long as 65 or 120 years. These taxa exhibit mass flowering (or gregarious flowering), with all plants in a particular species flowering worldwide over a several year period. The longest mass flowering interval known is 130 years, and is found for all the species Phyllostachys bambusoides (Sieb. & Zucc.). In this species, all plants of the same stock flower at the same time, regardless of differences in geographic locations or climatic conditions, and then the bamboo dies. The lack of environmental impact on the time of flowering indicates the presence of some sort of “alarm clock” in each cell of the plant which signals the diversion of all energy to flower production and the cessation of vegetative growth. This mechanism, as well as the evolutionary cause behind it, is still largely a mystery.

One theory to explain the evolution of this semelparous mass flowering is the predator satiation hypothesis. This theory argues that by fruiting at the same time, a population increases the survival rate of their seeds by flooding the area with fruit so that even if predators eat their fill, there will still be seeds left over. By having a flowering cycle longer than the lifespan of the rodent predators, bamboos can regulate animal populations by causing starvation during the period between flowering events. Thus, according to this hypothesis, the death of the adult clone is due to resource exhaustion, as it would be more effective for parent plants to devote all resources to creating a large seed crop than to hold back energy for their own regeneration.

A second theory, the fire cycle hypothesis, argues that periodic flowering followed by death of the adult plants has evolved as a mechanism to create disturbance in the habitat, thus providing the seedlings with a gap in which to grow. This hypothesis argues that the dead culms create a large fuel load, and also a large target for lightning strikes, increasing the likelihood of wildfire. Because bamboos can be aggressive as early successional plants, the seedlings would be able to outstrip other plants and take over the space left by their parents.

However, both have been disputed for different reasons. The predator satiation theory does not explain why the flowering cycle is 10 times longer than the lifespan of the local rodents, something not predicted by the theory. The bamboo fire cycle theory is considered by a few scientists to be unreasonable; they argue that fires only result from humans and there is no natural fire in India. This notion is considered wrong based on distribution of lightning strike data during the dry season throughout India. However, another argument against this theory is the lack of precedent for any living organism to harness something as unpredictable as lightning strikes to increase its chance of survival as part of natural evolutionary progress.

The mass fruiting also has direct economic and ecological consequences, however. The huge increase in available fruit in the forests often causes a boom in rodent populations, leading to increases in disease and famine in nearby human populations. For example, there are devastating consequences when the Melocanna bambusoides population flowers and fruits once every 30–35 years around the Bay of Bengal. The death of the bamboo plants following their fruiting means the local people lose their building material, and the large increase in bamboo fruit leads to a rapid increase in rodent populations. As the number of rodents increase, they consume all available food, including grain fields and stored food, sometimes leading to famine. These rats can also carry dangerous diseases such as typhus, typhoid, and bubonic plague, which can reach epidemic proportions as the rodents increase in number. The relationship between rat populations and bamboo flowering was examined in a 2009 Nova documentary Rat Attack.

In any case, flowering produce masses of seeds, typically suspended from the ends of the branches. These seeds will give rise to a new generation of plants that may be identical in appearance to those that preceded the flowering, or they may also produce new cultivars with different characteristics, such as the presence or absence of striping or other changes in coloration of the culms.

Soft bamboo shoots, stems, and leaves are the major food source of the giant panda of China, the red panda of Nepal and the bamboo lemurs of Madagascar. Rats will eat the fruits as described above. Mountain gorillas of Africa also feed on bamboo, and have been documented consuming bamboo sap which was fermented and alcoholic; chimps and elephants of the region also eat the stalks.

Timber is harvested from cultivated and wild stands and some of the larger bamboos, particularly species in the genus Phyllostachys, are known as "timber bamboos".

Harvesting

Bamboo used for construction purposes must be harvested when the culms reach their greatest strength and when sugar levels in the sap are at their lowest, as high sugar content increases the ease and rate of pest infestation.

Harvesting of bamboo is typically undertaken according to the following cycles:

1) Life cycle of the culm: As each individual culm goes through a 5–7 year life cycle, culms are ideally allowed to reach this level of maturity prior to full capacity harvesting. The clearing out or thinning of culms, particularly older decaying culms, helps to ensure adequate light and resources for new growth. Well-maintained clumps may have a productivity three to four times that of an unharvested wild clump.

2) Life cycle of the culm: Consistent with the life cycle described above, bamboo is harvested from two to three years through to five to seven years, depending on the species.

3) Annual cycle: As all growth of new bamboo occurs during the wet season, disturbing the clump during this phase will potentially damage the upcoming crop. Also during this high rain fall period, sap levels are at their highest, and then diminish towards the dry season. Picking immediately prior to the wet/growth season may also damage new shoots. Hence, harvesting is best at the end of the dry season, a few months prior to the start of the wet.

4) Daily cycle: During the height of the day, photosynthesis is at its peak, producing the highest levels of sugar in sap, making this the least ideal time of day to harvest. Many traditional practitioners believe the best time to harvest is at dawn or dusk on a waning moon. This practice makes sense in terms of both moon cycles, visibility and daily cycles.

Leaching

Leaching is the removal of sap after harvest. In many areas of the world, the sap levels in harvested bamboo are reduced either through leaching or postharvest photosynthesis. Examples of this practice include:

- Cut bamboo is raised clear of the ground and leant against the rest of the clump for one to two weeks until leaves turn yellow to allow full consumption of sugars by the plant.

- A similar method is undertaken, but with the base of the culm standing in fresh water, either in a large drum or stream to leach out sap.

- Cut culms are immersed in a running stream and weighted down for three to four weeks.

- Water is pumped through the freshly cut culms, forcing out the sap (this method is often used in conjunction with the injection of some form of treatment).

In the process of water leaching, the bamboo is dried slowly and evenly in the shade to avoid cracking in the outer skin of the bamboo, thereby reducing opportunities for pest infestation.

Durability of bamboo in construction is directly related to how well it is handled from the moment of planting through harvesting, transportation, storage, design, construction and maintenance. Bamboo harvested at the correct time of year and then exposed to ground contact or rain, will break down just as quickly as incorrectly harvested material.

Ornamental bamboos

There are two general patterns for the growth of bamboo: "clumping" (sympodial) and "running" (monopodial). Clumping bamboo species tend to spread slowly, as the growth pattern of the rhizomes is to simply expand the root mass gradually, similar to ornamental grasses. "Running" bamboos, on the other hand, need to be taken care of in cultivation because of their potential for aggressive behavior. They spread mainly through their roots and/or rhizomes, which can spread widely underground and send up new culms to break through the surface. Running bamboo species are highly variable in their tendency to spread; this is related to both the species and the soil and climate conditions. Some can send out runners of several meters a year, while others can stay in the same general area for long periods. If neglected, over time they can cause problems by moving into adjacent areas.

Bamboos seldom and unpredictably flower, and the frequency of flowering varies greatly from species to species. Once flowering takes place, a plant will decline and often die entirely. Although there are always a few species of bamboo in flower at any given time, collectors desiring to grow specific bamboo typically obtain their plants as divisions of already-growing plants, rather than waiting for seeds to be produced.

Regular maintenance will indicate major growth directions and locations. Once the rhizomes are cut, they are typically removed; however, rhizomes take a number of months to mature and an immature, severed rhizome will usually cease growing if left in-ground. If any bamboo shoots come up outside of the bamboo area afterwards, their presence indicates the precise location of the missed rhizome. The fibrous roots that radiate from the rhizomes do not produce more bamboo if they stay in the ground.

Bamboo growth can also be controlled by surrounding the plant or grove with a physical barrier. Typically, concrete and specially-rolled HDPE plastic are the materials used to create the barrier, which is placed in a 60–90 cm (2.0–3.0 ft) deep ditch around the planting, and angled out at the top to direct the rhizomes to the surface. (This is only possible if the barrier is installed in a straight line.) If the containment area is small, this method can be detrimental to ornamental bamboo as the bamboo within can become rootbound and start to display the signs of any unhealthy containerized plant. In addition, rhizomes can escape over the top, or beneath the barrier if it is not deep enough. Strong rhizomes and tools can penetrate plastic barriers, so care must be taken. In small areas, regular maintenance may be the best method for controlling the running bamboos. Barriers and edging are unnecessary for clump-forming bamboos, although clump-forming bamboos may eventually need to have portions removed if they become too large.

The ornamental plant sold in containers and marketed as "lucky bamboo" is actually an entirely unrelated plant, Dracaena sanderiana. It is a resilient member of the lily family that grows in the dark, tropical rainforests of Southeast Asia and Africa. Lucky bamboo has long been associated with the Eastern practice of feng shui. On a similar note, Japanese knotweed is also sometimes mistaken for a bamboo, but it grows wild and is considered an invasive species.

Uses

Khao lam (Thai: ข้าวหลาม) is glutinous rice with sugar and coconut cream cooked in specially-prepared bamboo sections of different diameters and lengths

The shoots (new culms that come out of the ground) of bamboo are edible. They are used in numerous Asian dishes and broths, and are available in supermarkets in various sliced forms, in both fresh and canned versions. The shoots of the giant bamboo (Cathariostachys madagascariensis) contain cyanide. Despite this, the golden bamboo lemur ingests many times the quantity of toxin that would kill a human.

The bamboo shoot in its fermented state forms an important ingredient in cuisines across the Himalayas. In Assam, India, for example, it is called khorisa. In Nepal, a delicacy popular across ethnic boundaries consists of bamboo shoots fermented with turmeric and oil, and cooked with potatoes into a dish that usually accompanies rice (alu tama in Nepali).

In Indonesia, they are sliced thin and then boiled with santan (thick coconut milk) and spices to make a dish called gulai rebung. Other recipes using bamboo shoots are sayur lodeh (mixed vegetables in coconut milk) and lun pia (sometimes written lumpia: fried wrapped bamboo shoots with vegetables). The shoots of some species contain toxins that need to be leached or boiled out before they can be eaten safely.

Pickled bamboo, used as a condiment, may also be made from the pith of the young shoots.

The sap of young stalks tapped during the rainy season may be fermented to make ulanzi (a sweet wine) or simply made into a soft drink. Bamboo leaves are also used as wrappers for steamed dumplings which usually contains glutinous rice and other ingredients.

Pickled bamboo shoots (Nepali: tama) are cooked with black eyed beans as a delicacy food in Nepal. Many Nepalese restaurant around the world serve this dish as aloo bodi tama. Fresh bamboo shoots are sliced and pickled with mustard seeds and turmeric and kept in glass jar in sun for the best taste. It is used alongside many dried beans in cooking during winter months. Baby shoots (Nepali: tusa) of a very different variety of bamboo (Nepali: Nigalo) native to Nepal is cooked as a curry in Hilly regions.

In Sambalpur, India, the tender shoots are grated into juliennes and fermented to prepare kardi. The name is derived from the Sanskrit word for bamboo shoot, karira. This fermented bamboo shoot is used in various culinary preparations, notably amil, a sour vegetable soup. It is also made into pancakes using rice flour as a binding agent. The shoots that have turned a little fibrous are fermented, dried, and ground to sand-sized particles to prepare a garnish known as hendua. It is also cooked with tender pumpkin leaves to make sag green leaves.

The empty hollow in the stalks of larger bamboo is often used to cook food in many Asian cultures. Soups are boiled and rice is cooked in the hollows of fresh stalks of bamboo directly over a flame. Similarly, steamed tea is sometimes rammed into bamboo hollows to produce compressed forms of Pu-erh tea. Cooking food in bamboo is said to give the food a subtle but distinctive taste.

In addition, bamboo is frequently used for cooking

utensils within many cultures, and is used in the manufacture of chopsticks. In modern times, some see bamboo tools as an eco-friendly alternative to other manufactured utensils.

Medicine

Bamboo is used in Chinese medicine for treating infections and healing.

It is a low-calorie source of potassium. It is known for its sweet taste and as a good source of nutrients and protein.

In Ayurveda, the Indian system of traditional medicine, the silicious concretion found in the culms of the bamboo stem is called banslochan. It is known as tabashir or tawashir in Unani-Tibb the Indo-Persian system of medicine. In English, it is called "bamboo manna". This concretion is said to be a tonic for the respiratory diseases. It was earlier obtained from Melocanna bambusoides and is very hard to get. In most Indian literature, Bambusa arundinacea is described as the source of bamboo manna.

Construction

In its natural form, bamboo as a construction material is traditionally associated with the cultures of South Asia, East Asia and the South Pacific, to some extent in Central and South America and by extension in the aesthetic of Tiki culture. In China and India, bamboo was used to hold up simple suspension bridges, either by making cables of split bamboo or twisting whole culms of sufficiently pliable bamboo together. One such bridge in the area of Qian-Xian is referenced in writings dating back 960 A.D. and may have stood since as far back as the 3rd century B.C., due largely to continuous maintenance.

Bamboo has also long been used as scaffolding; the practice has been banned in China for buildings over six stories but is still in continuous use for skyscrapers in Hong Kong. In the Philippines, the nipa hut is a fairly typical example of the most basic sort of housing where bamboo is used; the walls are split and woven bamboo, and bamboo slats and poles may be used as its support. In Japanese architecture, bamboo is used primarily as a supplemental and/or decorative element in buildings such as fencing, fountains, grates and gutters, largely due to the ready abundance of quality timber.

Various structural shapes may be made by training the bamboo to assume them as it grows. Squared sections of bamboo are created by compressing the growing stalk within a square form. Arches may similarly be created by forcing the bamboo's growth with the desired form, and costs much less than it would to assume the same shape in regular wood timber. More traditional forming methods, such as the application of heat and pressure, may also be used to curve or flatten the cut stalks.

Bamboo can be cut and laminated into sheets and planks. This process involves cutting stalks into thin strips, planing them flat, boiling and drying the strips, which are then glued, pressed and finished. Generally long used in China and Japan, entrepreneurs started developing and selling laminated bamboo flooring in the West during the mid 1990s; products made from bamboo laminate, including flooring, cabinetry, furniture and even decorations, are currently surging in popularity, transitioning from the boutique market to mainstream providers. The bamboo goods industry (which also includes small goods, fabric, etc.) is expected to be worth $25 billion by the year 2012. The quality of bamboo laminate varies between manufacturers and the maturity of the plant from which it was harvested (six years being considered the optimum); the sturdiest products fulfill their claims of being up to three times harder than oak hardwood, but others may be softer than standard hardwood.

Bamboo intended for use in construction should be treated to resist insects and rot. The most common solution for this purpose is a mixture of borax and boric acid. Another process involves boiling cut bamboo to remove the starches that attract insects.

Bamboo has been used as reinforcement for concrete in those areas where it is plentiful, though dispute exists over its effectiveness in the various studies done on the subject. Bamboo does have the necessary strength to fulfill this function, but untreated bamboo will swell from the absorption of water from the concrete, causing it to crack. Several procedures must be followed to overcome this shortcoming.

Several institutes, businesses, and universities are working on the bamboo as an ecological construction material. In the United States and France, it is possible to get houses made entirely of bamboo, which are earthquake and cyclone-resistant and internationally certified. In Bali, Indonesia, an international primary school, named the Green School, is constructed entirely of bamboo, due to its beauty, and advantages as a sustainable resource. There are three ISO standards for bamboo as a construction material.

In parts of India, bamboo is used for drying clothes indoors, both as the rod high up near the ceiling to hang clothes on, as well as the stick that is wielded with acquired expert skill to hoist, spread, and to take down the clothes when dry. It is also commonly used to make ladders, which apart from their normal function, are also used for carrying bodies in funerals. In Maharashtra, the bamboo groves and forests are called VeLuvana, the name VeLu for bamboo is most likely from Sanskrit, while Vana means forest.

Furthermore, bamboo is also used to create flagpoles for saffron-coloured, Hindu religious flags, which can be seen fluttering across India, especially Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, as well as in Guyana and Suriname.

Bamboo is used for the structural members of the India pavilion at Expo 2010 in Shanghai. The pavilion is the world’s largest bamboo dome, about 34 m in diameter, with bamboo beams/members overlaid with a ferro-cement slab, water proofing, copper plate, solar PV panels, a small windmill and live plants. A total of 30 km of bamboo were used. The dome is supported on 18-m-long steel piles and a series of steel ring beams. The bamboo was treated with borax and boric acid as a fire retardant and insecticide and bent in the required shape. The bamboo sections are joined with reinforcement bars and concrete mortar to achieve necessary lengths.

Furniture

Bamboo has a long history of use in Asian furniture. Chinese bamboo furniture is a distinct style based on millennia-long tradition.

Textiles

Because the fibers of bamboo are very short (less than 3mm), they are impossible to transform into yarn in a natural process.[28] The usual process by which textiles labeled as being made of bamboo are produced uses only the rayon, that is being made out of the fibers with heavy employment of chemicals. To accomplish this, the fibers are broken down with chemicals and extruded through mechanical spinnerets; the chemicals include lye, carbon disulfide and strong acids.[23] Retailers have sold both end products as "bamboo fabric" to cash in on bamboo's current ecofriendly cachet; however, the Canadian Competition Bureau[29] and the US Federal Trade Commission,[30] as of mid-2009, are cracking down on the practice of labeling bamboo rayon as natural bamboo fabric. Under the guidelines of both agencies, these products must be labeled as rayon with the optional qualifier "from bamboo".[30]

Paper

Bamboo fiber has been used to make paper in China since early times. A high quality hand-made paper is still produced in small quantities. Coarse bamboo paper is still used to make spirit money in many Chinese communities.

Bamboo pulps are mainly produced in China, Myanmar, Thailand and India and are used in printing and writing papers.[32] The most common bamboo species used for paper are Dendrocalamus asper and Bamboo bluemanea. It is also possible to make dissolving pulp from bamboo. The average fiber length is similar to hardwoods, but the properties of bamboo pulp are closer to softwoods pulps due to it having a very broad fiber length distribution. With the help of molecular tools, it is now possible to distinguish the superior fiber-yielding species/varieties even at juvenile stages of their growth which can help in unadulterated merchandise production.

Musical instruments

Bamboo's natural hollow form makes it an obvious choice for many instruments, particularly wind and percussion. There are numerous types of bamboo flute made all over the world, such as the dizi, xiao, shakuhachi, palendag and jinghu. In India, it is a very popular and highly respected musical instrument, available even to the poorest and the choice of many highly venerated maestros of classical music. It is known and revered above all as the divine flute forever associated with Lord Krishna, who is always portrayed holding a bansuri in sculptures and paintings. Four of the instruments used in Polynesia for traditional hula are made of bamboo: nose flute, rattle, stamping pipes and the jaw harp. Bamboo may be used in the construction of the Australian didgeridoo instead of the more traditional eucalyptus wood. In Indonesia and the Philippines, bamboo has been used for making various kinds of musical instruments, including the kolintang, angklung and bumbong. Traditional Philippine banda kawayan (bamboo bands) use a variety of bamboo musical instruments, including the marimba, angklung, panpipes and bumbong, as well as bamboo versions of western instruments, such as clarinets, saxophones, and tubas.[34] The Las Piñas Bamboo Organ in the Philippines has pipes made of bamboo culms. The modern amplified string instrument, the Chapman stick, is also constructed using bamboo. The khene (also spelled khaen, kaen and khen; Lao: ແຄນ, Thai: แคน) is a mouth organ of Lao origin whose pipes, which are usually made of bamboo, are connected with a small, hollowed-out hardwood reservoir into which air is blown, creating a sound similar to that of the violin. In the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar, the valiha, a long tube zither made of a single bamboo stalk, is considered the national instrument.

Water processing

Bamboo can be used in water desalination. A bamboo filter is used to remove the salt from seawater.

Transportation

Several manufacturers offer bamboo bicycles and longboards.

Landscaping

Bamboo is widely used in landscaping due to its ability to grow quickly in thick, tall sections. It makes an excellent privacy barrier, while also providing a nice aesthetic. However, unless properly maintained, bamboo may violate different public nuisance ordinances.

Depiction in Tattoos

Thanks to its longitudinal shape, the bamboo plant lends its form to spinal tattoos but also is a popular subject for body art generally.

Angling

Due to its flexibility bamboo is also used to make fishing rods. The split cane rod is especially prized for fly fishing.

Firecracker

Bamboo has been traditionally used in Malaysia as a firecracker called a meriam buluh or bamboo cannon. Four feet long sections of bamboo are cut and a mixture of water and calcium carbide are introduced. The resulting acetylene gas is ignited with a stick producing a loud bang.

Bamboo's long life makes it a Chinese symbol of longevity, while in India it is a symbol of friendship. The rarity of its blossoming has led to the flowers' being regarded as a sign of impending famine. This may be due to rats feeding upon the profusion of flowers, then multiplying and destroying a large part of the local food supply. The most recent flowering began in May 2006 (see Mautam). Bamboo is said to bloom in this manner only about every 50 years (see 28–60 year examples in FAO: 'gregarious' species table).

In Chinese culture, the bamboo, plum blossom, orchid, and chrysanthemum (often known as méi lán zhú jú 梅兰竹菊) are collectively referred to as the Four Gentlemen. These four plants also represent the four seasons and, in Confucian ideology, four aspects of the junzi ("prince" or "noble one"). The pine (sōng 松), the bamboo (zhú 竹), and the plum blossom (méi 梅) are also admired for their perseverance under harsh conditions, and are together known as the "Three Friends of Winter" (岁寒三友 suìhán sānyǒu) in Chinese culture. The "Three Friends of Winter" is traditionally used as a system of ranking in Japan, for example in sushi sets or accommodations at a traditional ryokan. Pine (matsu 松) is of the first rank, bamboo (také 竹) is of second rank, and plum (ume 梅) is of the third.

Bamboo, noble and useful

Bamboo, one of the “four gentlemen” (bamboo, orchid, plum blossom and chrysanthemum), plays such an important role in traditional Chinese culture that it is even regarded as a behaviour model of the gentleman. As bamboo has some features like upright, tenacity and hollow heart, people endow bamboo with integrity, elegance and plainness though it is not physically strong. Ancient Chinese poets wrote countless poems to praise bamboo, but actually they were truly talking about people like bamboo and express their understanding of what is a real gentleman should be like. According to Laws,an ancient poet Bai, Juyi (772-846) thought that to be a gentleman, a man doesn’t need to be physically strong, but he must be mentally strong. He must be upright, perseverant. Just as a bamboo is hollow-hearted, he should open his heart to accept anything of benefit and never have arrogance or prejudice. Bamboo is not only a symbol of gentleman, but also an important role in Buddhism. In the first century, Buddhism was introduced into China. As cannons of Buddhism don’t allow its believers to do anything cruel to animals, meat, egg and fish were not allowed in the diet. However, people need something nutritional to live, thus, the tender bamboo shoot (it is called “sǔn筍” in Chinese) became a good choice. The bamboo shoot is nutritional and eating it does not violate the cannon. With thousands of years’ development, how to eat bamboo shoot has become a part of cuisine system, especially for monks. A Buddhist monk named Zan Ning, wrote a manual of the bamboo shoot called “Sǔn Pǔ筍譜”. He offered descriptions and recipes for many kinds of bamboo shoots. Bamboo shoot has always been a traditional dish on Chinese’s dinner table, especially in southern China. In ancient time, as long as people have money to buy a big house with yard, they will always plant bamboos in their garden. Bamboo is a necessary element of Chinese culture, or even in the whole Asian civilization. People plant bamboos, eat bamboo shoots, paint bamboos, write poems for bamboos, and speak highly of gentlemen who are like bamboos. Bamboo, is not only a plant, but also a part of people’s life.

In Japan, a bamboo forest sometimes surrounds a Shinto shrine as part of a sacred barrier against evil. Many Buddhist temples also have bamboo groves.

In northern Indian state of Assam, the fermented bamboo paste known as khorisa is known locally as a folk remedy for the treatment of impotence, infertility, and menstrual pains.

Bamboo plays an important part of the culture of Vietnam. Bamboo symbolizes the spirit of Vovinam (a Vietnamese martial arts): cương nhu phối triển (coordination between hard and soft (martial arts)). Bamboo also symbolizes the Vietnamese hometown and Vietnamese soul: the gentlemanlike, straightforwardness, hard working, optimism, unity and adaptability. A Vietnamese proverb says: "When the bamboo is old, the bamboo sprouts appear", the meaning being Vietnam will never be annihilated; if the previous generation dies, the children take their place. Therefore, the Vietnam nation and Vietnamese value will be maintained and developed eternally. Traditional Vietnamese villages are surrounded by thick bamboo hedges (lũy tre).

The Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD) Chinese scientist and polymath Shen Kuo (1031–1095) used the evidence of underground petrified bamboo found in the dry northern climate of Yan'an, Shanbei region, Shaanxi province to support his geological theory of gradual climate change.

Other cultures

The ethnic group known as the Bozo of West Africa, take their name from the Bambara phrase bo-so, which means "bamboo house".

The bamboo is the national plant of St. Lucia.

Myths and legends

Several Asian cultures, including that of the Andaman Islands, believe humanity emerged from a bamboo stem. In the Philippine creation myth, legend tells that the first man and the first woman each emerged from split bamboo stems on an island created after the battle of the elemental forces (Sky and Ocean). In Malaysian legends a similar story includes a man who dreams of a beautiful woman while sleeping under a bamboo plant; he wakes up and breaks the bamboo stem, discovering the woman inside. The Japanese folktale "Tale of the Bamboo Cutter" (Taketori Monogatari) tells of a princess from the Moon emerging from a shining bamboo section. Hawaiian bamboo ('ohe) is a kinolau or body form of the Polynesian creator god Kāne.

Bamboo cane is also the weapon of Vietnamese legendary hero Saint Giong - who had grown up immediately and magically since the age of three because of his national liberating wish against Ân invaders.

An ancient Vietnamese legend (The Hundred-knot Bamboo Tree) tells of a poor, young farmer who fell in love with his landlord's beautiful daughter. The farmer asked the landlord for his daughter's hand in marriage, but the proud landlord would not allow her to be bound in marriage to a poor farmer. The landlord decided to foil the marriage with an impossible deal; the farmer must bring him a "bamboo tree of one-hundred nodes". But Buddha (Bụt) appeared to the farmer and told him that such a tree could be made from one-hundred nodes from several different trees. Bụt gave to him four magic words to attach the many nodes of bamboo: Khắc nhập, khắc xuất, which means "joined together immediately, fell apart immediately". The triumphant farmer returned to the landlord and demanded his daughter. Curious to see such a long bamboo, the landlord was magically joined to the bamboo when he touched it as the young farmer said the first two magic words. The story ends with the happy marriage of the farmer and the landlord's daughter after the landlord agreed to the marriage and asked to be separated from the bamboo.

In a Chinese legend, the Emperor Yao gave two of his daughters as a test for his potential to rule to the future Emperor Shun. Shun passed the test of being able to run his household with the two emperor's daughters as wives, and thus Yao made Shun his successors, bypassing his unworthy son. Later, Shun drowned in the Xiang River. The tears his two bereaved wives let fall upon the bamboos growing there explains the origin of spotted bamboo. The two women later became goddesses.

As a writing surface

Main article: Bamboo and wooden slips

Bamboo was in widespread use in early China as a medium for written documents. The earliest surviving examples of such documents, written in ink on string-bound bundles of bamboo strips (or "slips"), date from the fifth century BC during the Warring States period. However, references in earlier texts surviving on other media make it clear that some precursor of these Warring States period bamboo slips was in use as early as the late Shang period (from about 1250 BC).

Bamboo or wooden strips were the standard writing material during the Han dynasty, and excavated examples have been found in abundance.[40] Subsequently, paper began to displace bamboo and wooden strips from mainstream uses, and by the fourth century AD, bamboo had been largely abandoned as a medium for writing in China. Several paper industries are surviving on bamboo forests. Ballarpur (Chandrapur, Maharstra) paper mills use bamboo for paper production.

As a weapon

Bamboo is used in several East Asian and South Asian martial arts.

- In the ancient Tamil martial art of Silambam, fighters would hit each other rapidly with bamboo sticks.

- In the Japanese martial art Kendo, bamboo is used to make the Shinai sword.

- A bamboo stick can be made into a simple spear by sharpening one of the ends

- Archery longbow and recurve bow limbs are commonly crafted with flat ground bamboo, and make superior weapons for bowhunting and target archery.

7. BAMBOO GLUE

Bamboo Flooring Glue

1. Nontoxic Glue

Traditional plywood uses Urea Formaldehyde glue and Phenol glue. The danger in using this product indoors is the emission of formaldehyde and poisonous phenyl, which

affects the central nervous system. Many bamboo flooring manufactures import high quality European glue. The high strength of adhesion of this refined glue meets U.S. testing standards

for 3-ply laminated flooring ANSI-3 cycle-Test for flooring. Emissions meet the E1 standard. This is the reason why these products lead in the industry and are accepted and promoted in European, U.S.

and Japanese flooring markets.

-

2. Non-Formaldehyde Glue

This type is an imported glue is from Japan which is totally free from formaldehyde emission and special for Japanese market. After stringent testing by MLIT, this bamboo flooring produced has been approved of marketing in Japan by Ministry Approval.3. About Formaldehyde

a) Introduction

Formaldehyde is an important chemical used widely by industry to manufacture building materials and numerous household products. It is also a by-product of combustion and certain other natural processes. Thus, it may be present in substantial concentrations both indoors and outdoors.

Sources of formaldehyde in the home include building materials, smoking, household products, and the use of un-vented, fuel-burning appliances, like gas stoves or kerosene space heaters. Formaldehyde, by itself or in combination with other chemicals, serves a number of purposes in manufactured products. For example, it is used to add permanent-press qualities to clothing and draperies, as a component of glues and adhesives, and as a preservative in some paints and coating products.

In homes, the most significant sources of formaldehyde are likely to be pressed wood products made using adhesives that contain urea-formaldehyde (UF) resins. Pressed wood products made for indoor use include: particleboard (used as sub-flooring and shelving and in cabinetry and furniture); hardwood plywood paneling (used for decorative wall covering and used in cabinets and furniture); and medium density fiberboard (used for drawer fronts, cabinets, and furniture tops). Medium density fiberboard contains a higher resin-to-wood ratio than any other UF pressed wood product and is generally recognized as being the highest formaldehyde-emitting pressed wood product.

Other pressed wood products, such as softwood plywood and flake or oriented strandboard, are produced for exterior construction use and contain the dark, or red/black-colored phenol-formaldehyde (PF) resin. Although formaldehyde is present in both types of resins, pressed woods that contain PF resin generally emit formaldehyde at considerably lower rates than those containing UF resin.

b) Resources of Formaldehyde

Pressed wood products (hardwood plywood wall paneling, particleboard, fiberboard) and furniture made with these pressed wood products. Urea-formaldehyde foam insulation (UFFI). Combustion sources and environmental tobacco smoke. Durable press drapes, other textiles, and glues.

c) Health Effects

Formaldehyde, a colorless, pungent-smelling gas, can cause watery eyes, burning sensations in the eyes and throat, nausea, and difficulty in breathing in some humans exposed at elevated levels (above 0.1 parts per million). High concentrations may trigger attacks in people with asthma. There is evidence that some people can develop a sensitivity to formaldehyde. It has also been shown to cause cancer in animals and may cause cancer in humans. Health effects include eye, nose, and throat irritation; wheezing and coughing; fatigue; skin rash; severe allergic reactions. May cause cancer. -

4. International Standards for Formaldehyde Emission

a)U.S.A. Standards

With only 0.02 mg formaldehyde per cubic meter of air, the adhesive used to laminate the bamboo strips which form bamboo flooring and panels off-gasses 6.5 times less than allowed under the stringent European (E1) standards which are 0.13 mg per cubic meter of air. The European standards are stricter than the U.S. standards.

In November 1987, OSHA proposed that the occupational standard for formaldehyde exposure be reduced from 3 parts per million (ppm) to 1 ppm, averaged over an 8-hour workday; this proposal became law the following month. In May 1992, the law was amended, and the formaldehyde exposure limit was reduced to 0.75 ppm. (Information is available from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Public Affairs Office, Room N3647, 200 Constitution Avenue, NW., Washington, DC 20210. You may also contact the Public Affairs Office by calling 202-693-1999.)

Given .75ppm regulations and .0155 for JadeMask adhesive product, JadeMask is 48 x less than the allowance by American standards. Conversion to Parts Per Million by Volume:

The conversions from "0.02 mg of formaldehyde per cubic meter of air" to "ppmv (parts per million by Volume)."

At an ambient air pressure of 1 atmosphere and a temperature of 60 degrees F (15.56 degrees C), 0.02 mg of formaldehyde per cubic meter of air = 0.0149 ppmv

At an ambient air pressure of 1 atmosphere and a temperature of 70 degrees F (21.11 degrees C), 0.02 mg of formaldehyde per cubic meter of air = 0.0152 ppmv

At an ambient air pressure of 1 atmosphere and a temperature of 80 degrees F (26.67 degrees C), 0.02 mg of formaldehyde per cubic meter of air = 0.0155 ppmv

The molecular weight of formaldehyde, which is 30.03, was used in the conversions.

b) European Standards

E1=10mg/100g

c) Japanese Standards

F**** < 0.005 mg/m2h .

From the summer of 2003, Japan Construction Regulations are scheduled to change so that all laminated/prefinished building products (that is, any product using glue or arriving at the jobsite prefinished) must be officially certified under the JAS (Japan Agricultural Standard) formaldehyde standards. Products must show a JAS stamp or other equivalent certification. Products without this certification CANNOT BE USED in any Japanese construction.

All imports into Japan must therefore be certified individually on a container load by container load inspection basis or the foreign manufacturer MUST pass JAS inspection and become certified ON A PER PRODUCT BASIS. Each product category requires separate certification, so certification for one product category does not give the factory the right to stamp JAS seals on all products.

Please note the following quote from one of the industry papers, The Japan Lumber Reports: "If mills wish to continue to ship their laminated products to Japan, they need to be authorized based on the new JAS regulation. However, in Europe, the main supply region of this product, there is only one registered inspection organization to authorize -- the Japan Plywood Inspection Corporation (JPIC).

"JPIC is also in charge of inspecting other wood products for JAS so they may not be able to handle so many applications in a limited time for laminated products, which may hamper smooth transition to new JAS authorization. There are registered overseas inspection organizations in U.S.A., Canada and Australia individually but in Europe there is no such organization in each country since Europe is considered one unit. Thus, JPIC head quarters is the only place European mills apply for inspection and authorization."

Note that there is no mention of any inspection services for any Asian country. As far as is known, JPIC is covering Asia as well as Europe.

Building products subject to these regulations include, but are not limited to, flooring, wall paneling, ceiling paneling, finger-joint laminated board, plywood, laminated structural material, and doors.

There are three kinds of formaldehyde certification: JAS, JIS and Minister Approval. JAS and JIS certification can be obtained on only those products for which JAS and JIS have defined categories. (JAS and JIS product categories are more or less mutually exclusive.) Products that fall outside JAS and JIS product categories cannot receive JAS or JIS certification. All such products must be approved under Minister Approval criteria.

Both JAS and JIS have designated product categories. JAS product categories include plywood, flooring, laminated timber, LVL, structural panel, finger jointed structural lumber for platform construction. JIS product categories include MDF, glue, and finish, among others. There are also products which do not have applicable JAS or JIS categories (for example, doors).

d) Chinese Standards

Stipulated in the new regulations of building materials, the formaldehyde emission meets 1.5mg/L, which is equal to European E1 Standard.

8. DYI REFINISHING

Bamboo floors are some of the most durable and beautiful floors available. The texture and grain lend a sophisticated note to any space, and the stains available for bamboo floors are numerous. Refinishing the bamboo flooring requires a little more finesse.

DO IT YOURSELF - Instructions

- Sweep the entire bamboo floor area free of any dust, debris or contaminants before refinishing. Pay special attention to the areas below cabinet overhangs and hard to reach areas, like under molding and close to appliances.

- Rent a commercial disc floor sander from a home improvement store. These machines rent for the day or half day depending on the size of the floor-refinishing project. Ask the staff to assist with finding the correct grit sandpaper for bamboo floor refinishing.

- Sand the bamboo floor according to the instructions given and always apply gentle even pressure to the disc floor sander as the machine travels across the floor surface for an even refinishing.

- Use a tack cloth or mildly damp mop after sanding to remove any haze or dust from the freshly sanded surface. Take care again to reach all hard to access areas.

- Apply a polyurethane finish to the bamboo floor. This will seal and polish the newly refinished floor. Use mops to apply the sealer in long even strokes across the floor. Allow the coat to dry, sand the bamboo floor lightly again with the disc sander and repeat sealing. Do this three to four times for best results.

Ask different manufacturers, and you’ll get different answers to this question. However, a careful look at how bamboo flooring is made should provide us with a fairly good idea of whether or not it can be refinished.

When you sand down the surface prior to refinishing, these strands will tear out very easily. Damage can even be produced when 100 grit sandpaper is used that is much more forgiving grit than would be used if you actually had to refinish an entire floor. Fibers can tear out at the edges. The next problem is the formaldehyde so commonly used in bamboo flooring production. When you sand the floor, this toxic chemical is turned to dust. Not only will the stench be unbearable, but there may be a health risk if eye and throat irritation is felt. The dust will end up everywhere, contaminating your house as well as lungs.

On the topic of glue, so much of it is used in bamboo flooring (as much as 20% content) that a sanded down plank will look hideous, covered in glue pockets.

Since bamboo is not as durable as manufacturers would have us believe, you will eventually have to do something about the dented and scratched surface. If you can’t refinish it, you will have to replace it

9. PALM OIL - RECYCLED

From waste to wares

By CHERYL POO

star2@thestar.com.my

New uses for oil palm biomass.

EVERY year, millions of tonnes of organic waste – forest and mill residues as well As agricultural waste, among others – are generated. The oil palm sector alone contributes to over four-fifths of the problem of biomass overload, leaving operators with the headache of disposal arrangements, transportation and cost. Today, however, oil palm waste is turning into a lucrative stream of income for operators and new industry players who are transforming the scraps into useful products while alleviating the issue of disposal at the same time.

Palm-trunk flooring panels feature attractive wood grains and come in various finishes, such as (from left) mahogany, natural and wenge. Other colours include light oak, mahogany and medium walnut. Faza Solution is one company that is tapping into the abundant resource, having been in oil palm research and development for the past decade. “We did a lot of research on the waste, finding ways to put it to good use to enhance people’s lives,” said director Khairil Faizi. The company obtains palm waste such as oil palm fronds and trunks, empty fruit bunches, palm kernel shells, palm kernel cakes and palm oil mill effluent from planters and mill operators. It then commissions different manufacturers to process the raw materials into various products. “We understand that environmental groups are concerned about global forest loss and climate imbalances. Our work has a strong focus to alleviate those problems, and in doing that, utilise waste and create useful products from it,” Khairil explained. “We started by creating animal feed pellets from oil palm fronds, which yielded good results. Buyers started asking us for more products from oil palm biomass.”

Palm flooring

What started as an attempt to replace livestock food drew in such strong demand from the agricultural industry that Faza Solution was compelled to innovate other new products, namely flooring panels and palm pulp paper products. Sporting a distinctive grain pattern that runs in a single direction across the panel, palm wood flooring is claimed to be “superior to standard requirements”.

Empty fruit

bunches are turned into pulp sheets and used for making palm-based paper, containers, kitchen utensils and moulds. The stringent standard imposed

includes the cold check, where each finished panel is exposed to 10 cycles of extreme temperatures, to test against cracking. In the chemical test, the flooring panel must withstand a 24-hour

exposure to household substances such as vinegar, lemon juice, ketchup, coffee, olive oil and alcohol, as well as an hour of mustard and watered-down detergent. This is to test the panels against

cracking. “If there’s no noted damage after the 24-hour exposure, we

deduce that our products are sturdy enough,” Khairil explained. “Our

strategy is to develop and commercialise palm materials as a new source for flooring. Most people would not have imagined that there would be a substitute for timber-based furnishing and

fittings.” He added that engineered palm

flooring is more durable and impact-resistant than timber flooring. Wooden flooring is said to shrink and expand following temperature changes. Engineered palm flooring, however, is said to remain

sturdy. “Each panel is manufactured with 10 layers of UV coating

which strengthens it. Further- more, the palm material is infused with resin to increase resistance to hairline cracks,” Khairil explained. “In fact, the natural grain texture keeps the palm panel strong so it does not succumb to

‘knots’ and other defects that take the strength out of the material. Plus, no additional maintenance is necessary. Just treat it as you would an ordinary floor. Sweep and mop as you see

fit.” The product, however, is not commercially available yet as Faza

Solution’s marketing plans are still in the works. “Palm wood flooring

is still very new in our market but this is the direction that the world is moving into right now. Our stocks are limited at the moment, as we have just finalised testing,” explained

Khairil. “We are making headway with governmental corporations and

have installed palm wood flooring in their buildings so that they can test out what we have built. Once we establish ourselves among Government departments, we’ll move on to the private sector.

We are aware that there are developers out there who are keen on green technology. We can meet those needs.” He added that the flooring is also available to residential house owners (more information is

available at oilpalmproducts.com). Although the pricing has yet to

be determined, Khairil admitted that palm flooring would cost slightly more than conventional timber flooring as it is still new in the market. “Much has gone into research and developmental costs. However, in the long run, as more citizens

start to experience the viability of our products, pricing will be lowered,” Khairil said.

Palm paper

He said the public needs to be aware of the alternatives offered by palm products, such as palm pulp paper products which can replace those made from wood.

Empty fruit bunches (EFB) are

shredded into thin strips of fibre and turned into pulp. The pulp is then compressed to form writing materials, food containers, kitchen utensils and cutlery. It can also be turned into disposable

lunch boxes and food trays,

which can replace those made from polystyrene. “No additives are

included in the

formula. There are just four to five machines to crush and compress the EFB into plastic-replacement moulds and brown paper sheets,” Khairil explained. "Polystyrene, when hot, tends to release

toxins which can be hazardous. But these items made from EFB are non-toxic, biodegradable and chemical-free.” To confirm that these products are, in fact, biodegradable, Khairil suggested that they be

buried in the ground after usage. “In three to four months’ time,

everything would have completely disappeared,” he said. “With low lignin and high fibre content, as well as a good resemblance to hardwood fibres, palm-based paper is strong. The raw material

it’s derived from is itself sturdy.” At this point, Faza

Solution’s partner manufacturers have produced sheets of brown paper, which have yet to take the form of proper stationery items. Like palm flooring, these products are not yet released to the general market as Faza

Solution is in the process of commissioning manufacturers to produce the end products. “Palm paper should be available in bookstores and local convenience stores by August,” he

shared. “As these are Malaysian products, we hope to stir up local awareness before bringing them to the world. “Biomass is a vast arena and we can do a lot of good with it. We’re not even inventing anything

new, just enhancing existing products. By using these environmentally friendly products, people are not just helping themselves, but the next generation too.”

RESANDING BAMBOO: A TRICKY PROPOSITION

By Avi Hadad

Bamboo is a really tricky material to work with, from the challenges of cutting and milling it into a floor, then acclimating and installing it, and finally the sand and finish. I will walk you through the basic steps of a refinish we did on a solid prefinished bamboo floor; the floor was a local public organization, so it was in a bad condition, as you can see here:

I hope this helps those of you who have never sanded a bamboo and those who have but had trouble with it.

- The first cut should be at a higher grit than your usual 36 or 50. That is because of two reasons: it is bamboo and it is a factory-finished product. Bamboo scratches really easily, so we don't want to put scratches in it more than necessary. Prefinished floors tend to sand better starting at a higher grit. So the first cut was 60. In this case, the scratches were so deep and the wear-and-tear was so pronounced that 60 was our choice. We would have started with 80 if the condition of the floor were better. Here's the floor while we were sanding with the big machine:

- If we had to cut this floor at a 7 degree angle, we would have used 80. When you cut a floor, the big machine is creating a more aggressive scratch pattern on the wood fibers. Any scratch you will put in at an angle will be very hard to take out. Keep that in mind.

- Make sure you vacuum thoroughly between every step of sanding. Keeping the floor clean will give you more control over the consistency of your scratch pattern.